Mock grant proposal written in Spring 2019

Background

In recent years, scientists have begun to investigate the effects of hippocampal abnormalities on behavior, even though this structure has historically been implicated solely in the conversion of short-term memories to long-term memories (Opitz, 2014). Many of these studies have been inconclusive about the affective change in neo-h lesioned animals when studied as infants, juveniles, and adults in response to various stimuli (videos, socially aversive objects, etc.), but trends have been shown (Bliss-Moreau et. al, 2010; Bliss-Moreau et. al, 2011A; Bliss-Moreau et. al, 2011B).

However, one study was able to fine significant effects of hippocampal lesions on emotional regulation. In the study, neonatal hippocampal lesions were shown to increase anxiety behaviors in rhesus monkeys during the human intruder task (Raper et. al, 2017). Thus, more research should be done to investigate these effects. This kind of research is important because it can help understand the effects of damage to/an underdeveloped hippocampus in terms of emotional reactivity and psychological disorders

Hypothesis

Rhesus macaques with neonatal hippocampal lesions will experience altered emotional reactivity in response to social fear stimuli.

Specific Aims

This hypothesis leads me to make the following predictions; Neo-H monkeys will be more emotionally reactive than control monkeys in response to social fear stimuli, Neo-H monkeys and controls will not differ significantly in their fear responses to innate and learned fear stimuli, and Neo-H monkeys will respond to fear with self-directed behavior and stereotypies, whereas control monkeys will respond with anxiety behaviors.

Subjects. Subjects will be pulled from a group of rhesus macaques at Yerkes National Primate Research Center who were administered either a sham operation at two weeks of age (control), or a hippocampal lesion using bilateral ibotenic acid injections at two weeks of age (Neo-H). The subjects are now adults (five years of age or older).

There are eight control monkeys (four male, four female) and eight Neo-H monkeys (five male, three female). Each monkey will go through six trials of the object responsiveness task.

Object Responsiveness Task. Each monkey will be placed in a modified lab care cage with which they are familiar. The front of the cage will have open bars and access to a metal platform where the objects and food items will be placed. A sliding black cover will be placed over the bars and lifted by machine when the trial starts. There will be four sections of each trial, and each trial will last 2 minutes; section one is a baseline where there is no object on the platform, section two is the neutral object (similar in appearance to the fear object) with a grape placed in front of it, section three is a grape alone, and section four is the fear object with a grape placed in front of it. A grape is used because of its status as a highly desired food object.

Social fear stimuli. The first pair of social fear objects is a Mr. Potato Head with all parts attached (fear) or a Mr. Potato Head with only feet attached for stability (neutral). The second pair of social fear objects is a little girl doll (fear) or an Amish doll (neutral).

Innate fear stimuli. The first pair of innate fear stimuli is a rubber snake (fear) or a coiled-up hose (neutral). The second pair of innate fear stimuli is a rubber spider (fear) or a dog toy with ribbons attached (neutral).

Conditioned fear stimuli. The first pair of conditioned fear stimuli is a pair for leather handing gloves (fear) or a pair of latex gloves (neutral. The second pair of conditioned fear stimuli is a capture net (fear) or a mop (neutral).

We will measure the latency to take the grape in each trial, the time spent manipulating the objects, and the behavioral responses of the monkeys.

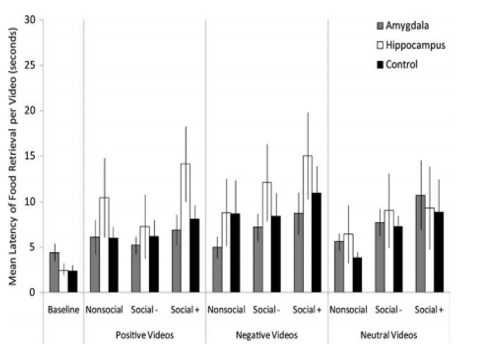

Figure 1. Food retrieval latency in response to videos. Data columns predict the average time to retrieve food per video type; error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Note that the figure uses raw data for the ease of interpretation, although log transformed data were analyzed.

Figure (From Bliss-Moreau, Bauman, & Amaral, 2011)

References

Bliss-Moreau E, Bauman MD, & Amaral DG (2011) Neonatal amygdala lesions result in globally blunted affect in adult rhesus macaques. Behavioral Neuroscience, 125(6), 848-858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025757

Bliss-Moreau E, Toscano JE, Bauman MD, Mason WA, & Amaral DG (2011) Neonatal amygdala lesions alter responsiveness to objects in juvenile macaques. Neuroscience, 178, 123-32. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.038

Bliss-Moreau E, Toscano JE, Bauman MD, Mason WA, & Amaral DG (2010) Neonatal amygdala or hippocampus lesions influence responsiveness to objects. Developmental Psychobiology, 52, 487-503. 10.1002/dev.20451

Opitz B (2014) Memory function and the hippocampus. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, 34, 51-59. doi.10.1159/000356422

Raper J, Wilson M, Sanchez M, Payne C, & Bachevalier J (2017) Increased anxiety-like behaviors, but blunted cortisol stress response after neonatal hippocampal lesions in monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 76, 57-66. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.011